During the bi-yearly review of my setup, I realized I was running a Linux machine without full disk encryption. The encryption of the disk needed to be done ASAP, but I was not willing to reinstall the whole operating system to achieve that.

Solution? I came up with an interesting way to encrypt my existing Linux installation without reinstalling it. And with zero downtime too: while I was moving my data and encrypting it, I was still able to use my computer productively. In other words, the process works on the fly!

Requirements

There are three requirements for this guide:

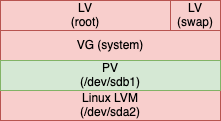

- The Linux installation already lives in an unencrypted LVM setup

- Some space to store your data (in another partition or on an external disk) with equal or more capacity than the LVM partition you are trying to encrypt

- Do a backup of the hard drive and store it somewhere (another disk, NFS, S3… I suggest using Clonezilla for this purpose). And don’t forget to test your backup.

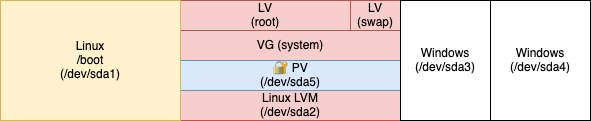

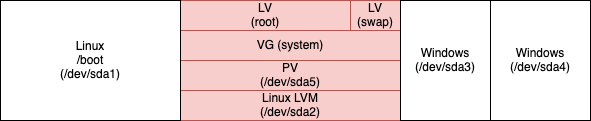

Initial situation

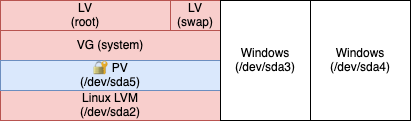

As a starting point, let’s visualize the partitions of my hard disk:

/boot will remain a separate partition for the time being (we will discuss it later).

After we will be finished, the resulting hard disk layout is referenced as LVM on top of an encrypted LUKS encrypted partition.

Install the required tools

Since I am already using LVM, the only package I am missing is cryptsetup: find it in your distribution repositories and install it.

Encryption of existing Linux LVM partition

In a nutshell, what we are going to do in LVM terms:

- Add the external disk (

/dev/sdb1in my case) to the VG - Move the PE from the internal disk PV to the external disk PV

- Remove the internal disk PV from the VG

- Create a LUKS encrypted container in the internal disk, a PV in it, and add the created PV to the VG

- Move the PE from the external disk PV to the internal disk PV

- Remove the external disk PV from the VG

- Configure the bootloader to access the encrypted PV

In the following sections, we are going to describe every step in detail.

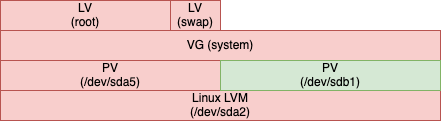

1. Add the external disk (/dev/sdb1 in my case) to the volume group

Let’s create a physical volume in the external disk and add it to the volume group (in my case this is called ‘system’):

# pvcreate /dev/sdb1

# vgextend system /dev/sdb1

2. Move the physical extents from the internal disk physical volume to the external physical volume

This is a time-consuming operation: we will transfer all the physical extents from the internal disk physical volume to the external disk physical volume:

# pvmove /dev/sda5 /dev/sdb1

The command will periodically output the percentage of completion.

The speed of the process depends on multiple factors, overall others: hard disk transfer throughput and size of the data to move.

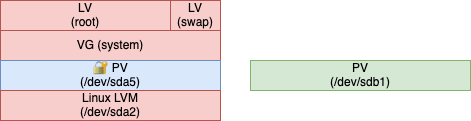

3. Remove the internal disk physical volume from the volume group

Now the physical volume in the internal disk is empty: we can remove it from the volume groups and remove the physical volume from it:

# vgreduce system /dev/sda5

# pvremove /dev/sda5

4. Create a LUKS encrypted container in the internal disk, a physical volume in it, and add the created physical volume to the volume group

Our data is completely stored on the physical volume that is in the external disk: we are halfway through.

Let’s wipe the internal disk partition that was holding our unencrypted data:

# cryptsetup open --type plain /dev/sda5 container --key-file /dev/urandom

Now we need to create an encrypted LUKS container to hold the new internal disk PV.

Different options can be selected, depending on the distribution you are running, the bootloader, and the version of cryptsetup you are using (e.g. LUKS2 works only with cryptsetup ≥ 2.1.0).

I choose:

- XTS cipher

- 512 bits key size

- LUKS1 (so I can remove the separate

/bootpartition later)

A password will be asked (do not lose it):

# cryptsetup -v --verify-passphrase -s 512 luksFormat /dev/sda5

This password will be used for every subsequent mounting of the root volume (e.g. on boot, so choose carefully).

Let’s now create a physical volume into the container and then add the physical volume to the volume group:

# cryptsetup luksOpen /dev/sda5 dm_crypt-1

# pvcreate /dev/mapper/dm_crypt-1

# vgextend system /dev/mapper/dm_crypt-1

5. Move the physical extents from the external disk physical volume to the internal disk physical volume

We are now going to reverse the direction of the data flow: the physical volume in the internal disk is now ready to hold our data again.

Let’s move the physical extents from the external disk PV to the internal disk physical volume. Again, this is a time-consuming operation that depends on the same factors outlined above:

# pvmove /dev/sdb1 /dev/mapper/dm_crypt-1

As stated before, the command will periodically output the percentage of completion.

6. Remove the external disk physical volume from the volume group

Our data is now entirely on the internal disk physical volume (this time encrypted, though). We need to remove the external disk physical volume from the volume group and remove the physical volume on it:

# vgreduce system /dev/sdb1

# pvremove /dev/sdb1

It is considered good practice to completely wipe /dev/sdb1 now, as it was containing our unencrypted data.

7. Configure the bootloader to access the encrypted physical volume

The final step is to inform the bootloader that the root file-system is now on an encrypted partition.

Depending on your distribution, there are different ways to inform the bootloader.

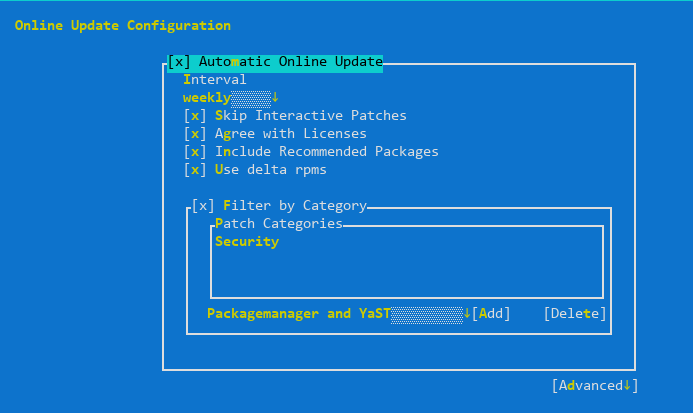

My distribution of choice (openSUSE) features GNU GRUB and initrd. In this case, the specific instructions are:

- Create

/etc/crypttaband insert the name of the encrypted LUKS container with the UUID of the partition on the disk (check which one withls /dev/disk-by-uuid):

# ls -l /dev/disk/by-uuid/ | grep sda5

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 10 Nov 13 21:27 45a4cbf0-da55-443f-9f2d-70752b16de8d -> ../../sda5

# echo "dm_crypt-1 UUID=45a4cbf0-da55-443f-9f2d-70752b16de8d" > /etc/crypttab

- Regenerate initrd with:

# mkinitrd- Reinstall GRUB with:

grub2-mkconfig -o /boot/grub2/grub.cfg && grub2-install /dev/sda

initrd will now ask at every boot the same password you used to create the LUKS container.

Right now our root volume is encrypted, except for /boot which is left unencrypted. Leaving /boot unencrypted brings some benefits:

- Unattended LUKS unlock via keyfile (stored, for example, in a USB key)

- LUKS unlock via the network (authenticate via SSH to provide the LUKS password as implemented in dropbear-initramfs)

One big drawback: having /boot unencrypted is vulnerable to the evil maid attack. But simple remediation can be put in place: let’s discover it in the next section.

Optional: remove the separate /boot partition and achieve full disk encryption (FDE)

Depending on your security model, on the bootloader you are using, on the LUKS version your container is using, it might be more secure to make /boot part of the encrypted volume.

In my case, I decided that I wanted full disk encryption so I moved /boot into the encrypted volume.

The idea here is to:

- Create a copy of

/bootinto the LVM volume

# cp -rav /boot /boot-new

# unmount /boot

# mv /boot /boot.old

# mv /boot-new /boot

- Remove the

/bootpartition from/etc/fstab:

# grep -v /boot /etc/fstab > /etc/fstab.new && mv /etc/fstab.new /etc/fstab- Modify GRUB to load the boot loader from an encrypted partition:

# echo "GRUB_ENABLE_CRYPTODISK=y" >>/etc/default/grub- Provision a keyfile to avoid typing the unlocking password twice.

We are now in a particular situation: GRUB needs a password to unlock the second stage of the bootloader (we just enabled it). After the initrd has loaded, it needs the same password to mount the root device.To avoid typing the password twice, there is a handy explanation in the openSUSE Wiki: avoid typing the passphrase twice with full disk encryption.

Be sure to follow all the steps. - Install the new bootloader:

- Provision a keyfile to avoid typing the unlocking password twice.

# grub2-mkconfig -o /boot/grub2/grub.cfg && grub2-install /dev/sda

Everything now is in place: all the data is encrypted at rest.

Only one password will be asked: the password that you used to create the LUKS container. GRUB will ask it every time you boot the system, while initrd will use the keyfile and will not ask for it.